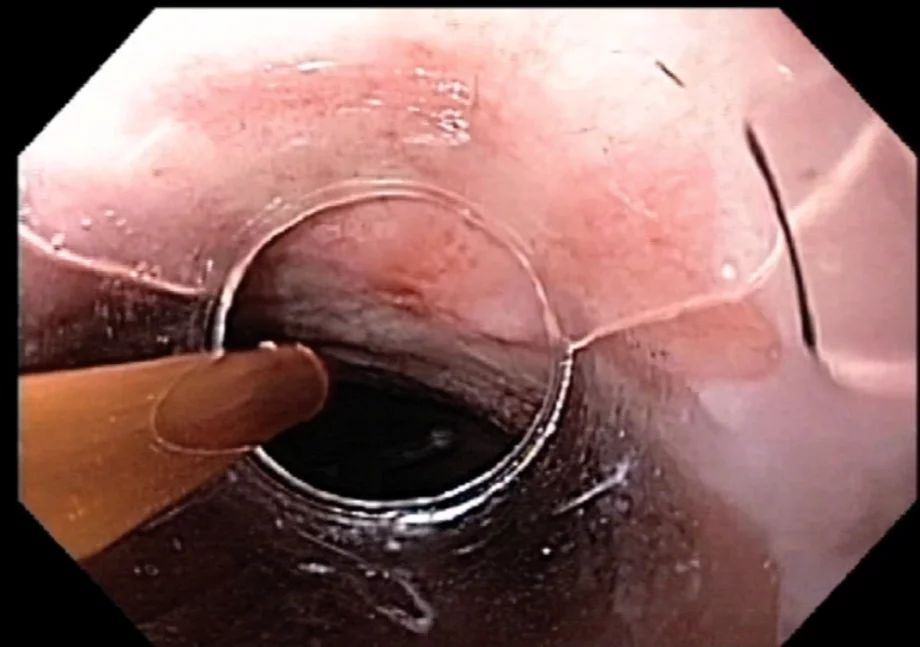

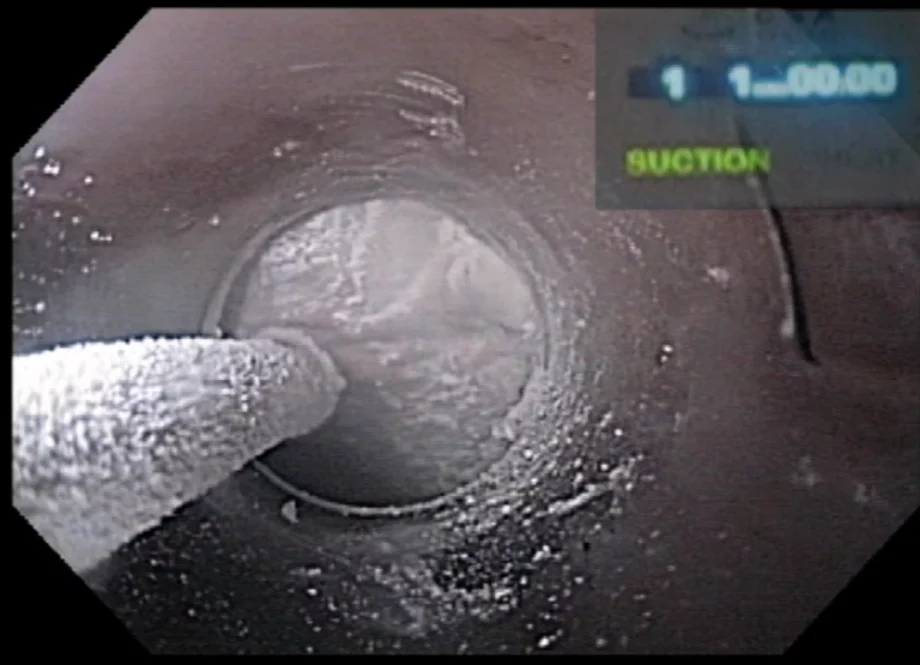

Barrett’s esophagus is a precursor lesion to adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Esophagectomy is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Several techniques have been developed to ablate or remove precancerous or early neoplasia in the esophagus. In this issue of the WEO newsletter, Dr Amitabh Chak of University Hospitals, Cleveland, USA, describes his approach to ablation of these lesions using cryotherapy. Other modalities will be covered in the near future.

Nalini M Guda MD, FASGE, FACG, AGAF

Editor, WEO Newsletter

Dr Amitabh Chak, Brenda and Marshall B. Brown Master Clinician in Innovation and Discovery at University Hospitals, Cleveland, USA , shares his expert advice on endoscopic cryoablation of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer.